Generate A Zip Asynchronously With VertX

Don't block the event loop! Photo by Stephen Hateley on Unsplash

Don't block the event loop! Photo by Stephen Hateley on Unsplash

What Does It Mean To Generate A Zip Server Side?

One of my reflexes, when I try to do something I’ve never done before is first to query Google to have an idea if someone already encountered the problem and also get a rough idea about the various strategies to solve my problem. When I query “generate zip in java servlet”, we quickly end up on solutions that make use of the ZipOutStream and usually either store the result into an array of bytes (very bad solution) or wrap the servlet response with the ZIP output stream.

The first solution then limits the generation of the file to the size of the JVM heap free space. The second solution is better as it writes directly to the output. It can be written very simplistically like this:

@Override

protected void doGet(HttpServletRequest request, HttpServletResponse response) throws ServletException {

// The path below is the root directory of data to be

// compressed.

String path = getServletContext().getRealPath("data");

File directory = new File(path);

String[] files = directory.list();

response.setContentType("application/zip");

response.setHeader("Content-Disposition", "attachment; filename=\"DATA.ZIP\"");

response.setHeader("transfer-encoding", "chunked");

try (ZipOutputStream zos = new ZipOutputStream(response.getOutputStream())) {

byte[] bytes = new byte[2048];

for (String fileName : files) {

String filePath = directory.getPath() + FILE_SEPARATOR + fileName;

try (FileInputStream fis = new FileInputStream(filePath)) {

zos.putNextEntry(new ZipEntry(fileName));

int bytesRead;

while ((bytesRead = fis.read(bytes)) != -1) {

zos.write(bytes, 0, bytesRead);

}

}

}

} catch (IOException e) {

throw new ServletException(e);

}

}

If this solution works in most cases where we just want to generate small zip files, it raises a problem in the case of big zip files where it blocks a servlet just for generating a big zip file. Another solution would be to generate that file in a separate thread and, once ready, send it to the client. We would still need to store the result either in memory or on the disk, which should not be necessary.

The solution that I will describe in this post takes another approach and uses the Vert.x toolbox to generate that file asynchronously.

Vert.x The Asynchronous Toolkit

Vert.x is described as “a toolkit for building reactive applications on the JVM”. If you don’t know it, have immediately a look at this small tutorial, which will allow you to build your first Hello World application.

Coming from a standard JEE background, it can sometimes be quite difficult to adopt the reactive coding model and to deal with asynchronous calls. It’s definitely another way of thinking programming, and it took quite a time for me to figure out how to do that first asynchronous exercise correctly.

Vert.x is architectured around an event loop that handles the events as they arrive. Like in the good old Win32 GUI, if you stop that loop, then the UI freezes, and usually, you don’t want the user to destroy the mouse while trying to click on that button! With Vert.x, it’s the same: if you block the event loop, you block all the users that are accessing the server, hence the golden rule of Vert.X:

Do not block the event loop! - Tim Fox

In our example, if we were to generate our ZIP in the event loop, it may be problematic as I/O would be blocking and it takes time to assemble a ZIP with lots of files in it.

Executing Blocking Code in Vert.x

There are several ways to execute blocking code in Vertx, and we will focus only on one of them here. When you are on the event loop (like when you’re writing a routing handler for instance), you can write the following:

vertx.executeBlocking(promise -> {

// Call some blocking API that takes a significant amount of time to return

String result = someAPI.blockingMethod("hello");

promise.complete(result);

}, res -> {

System.out.println("The result is: " + res.result());

});

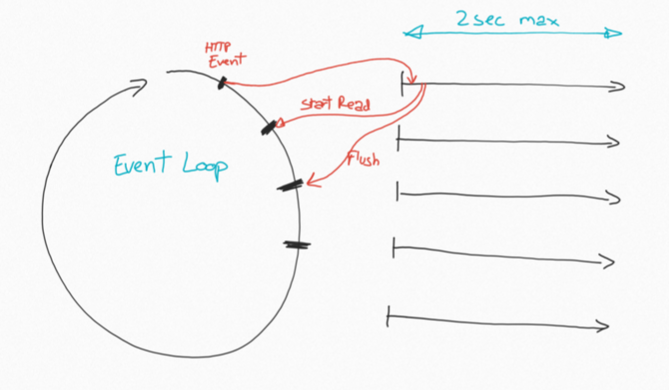

When calling that code, the event loop will schedule the call on a worker thread and run the callback when finished. It means that even if your code is blocking, the event loop will continue to handle the events that are sent to it (http events, for instance). The other limit that we have here is that the time to run that code should be reasonable. What is reasonable? No more than a few seconds. If it lasts too long, we will have errors like this in the logs:

WARNING: Thread Thread[vert.x-worker-thread-0,5,main]=Thread[vert.x-worker-thread-0,5,main] has been blocked for 2048 ms, time limit is 2000 ms

So, even if we have a very long zip, we are not allowed to work more than 2 seconds! There are alternatives like managing your own thread pool that would interact with the event loop through messages sent on the event bus, but we don’t want to come to that end: we can find something simpler.

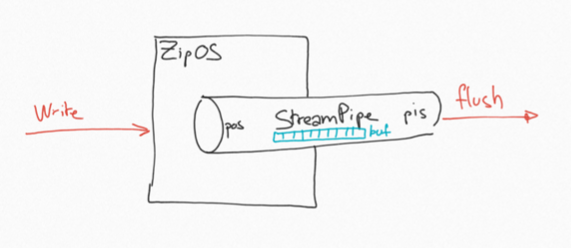

Building Our Conversion Pipe

To generate a ZIP in Java, we need to write bytes to a ZipOutputStream and then read it from the wrapped OutputStream. That is called a pipe, and in Java, we can configure it up with this code:

PipedOutputStream pos = new PipedOutputStream();

ZipOutputStream zos = new ZipOutputStream(pos);

InputStream pis = new PipedInputStream(pos, 8192);

The following schema explains it more visually:

In order to use that pipe correctly, we have to write data in the input, and regularly flush the data from the PipedInputStream. Those two actions have to happen in parallel as we have a fixed buffer (8KB) defined in the pipe. If it doesn’t happen in parallel, the write may be stuck because our pipe is full: we don’t want to be blocked!

The Vert.x documentation explains that a recommended way to handle Streams is to implement the ReadStream<?> interface. The code to call our pipe could then be as simple as:

ZipGenerator zip = new ZipGenerator(vertx, files).endHandler( ... );

Pump.pump(zip, response).start();

We now have our 3 constraints for our ZipGenerator:

- Every unit of work must not last more than 2s

- We have to find a way to run things concurrently

- It must implement the

ReadStream<Buffer>interface

Let’s Loop Now!

If we want to limit the time that we spend reading the source, we will have to do it iteratively i.e., in a loop. Instead of using a regular while/for control structure, we will use Vert.x event loop to emulate it. The pattern is the following:

private void doRead() {

vertx.executeBlocking(promise -> {

context.runOnContext(v -> doRead());

promise.complete();

}, v -> {});

}

That is like a recursive function: the difference lies in the fact that we delegate the next call to ourselves to the event loop. To ease reading, I’ve introduced two helper methods in my code so that it can now be read like this:

private void doRead() {

vertx.executeBlocking(promise -> {

next(this::doRead);

promise.complete();

}, noop());

}

It may seem overkill, but when you read it, you understand better the intent of the code… and in recursive programming, being precise with your intents is priceless!

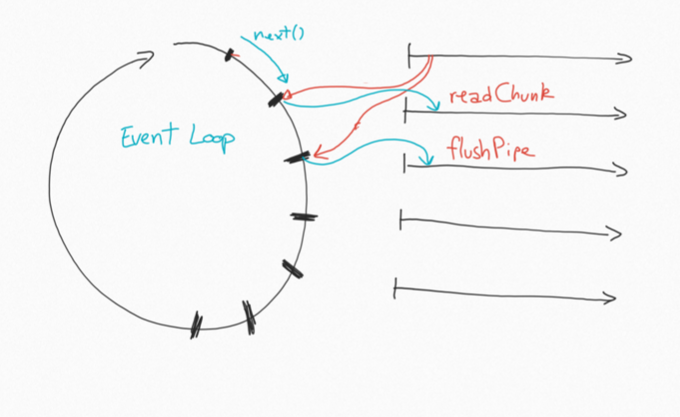

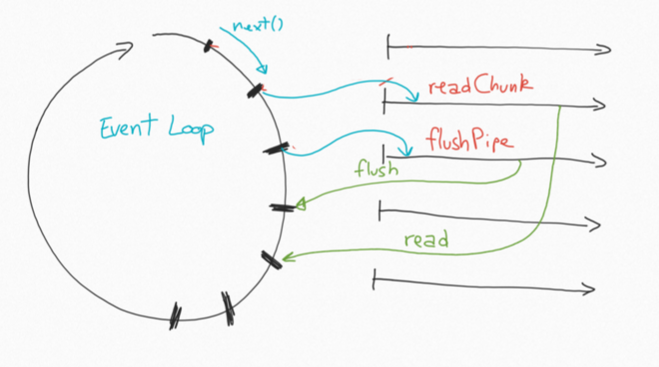

Another place where the event loop will help us is when we have to run things in parallel. If we can guarantee that the time to accomplish a task is finite, non-blocking and small, then doing it sequentially is the same as doing it in parallel. For instance, to start our two tasks, we can use the following code:

private void start() {

vertx.executeBlocking(promise -> {

next(this::startReading);

next(this::doFlushPipe);

promise.complete();

}, noop());

}

The following schema explains it probably better:

At the next loop tick, the event that we just created will be executed by the event loop thread. We will apply the same pattern to recurse to other methods if needed:

The two methods are then called sequentially, and they will start their small work on separate threads. The flushPipe method may end up faster than the readChunk one, but we do not really care. As long as our generator is active, we want to flush our pipe continuously.

The read loop will continue until our source is completely read. The flush loop will stop when the status of our generator will be CLOSED. The state of the generator is the only shared stated between the possible threads and is only written by one of the loops, so it’s thread-safe.

In the end, we just have to implement the ReadStream<Buffer> interface:

- the

handler()method will be used to trigger the start of the reading: as soon as we have something that will consume us, we can read. - the

pause()andresume()methods just update the state of our generator. - we have to call the registered

endHandleronce finished of course: it’s the handler that will close theHttpResponsebuffer.

Conclusion

As a more traditional Java developer, not used to functional programming, it took me quite some time to figure out how to correctly loop and handle the two paths of execution in that handler.

Reactive programming is definitely another programming mindset that you have to embrace when using a toolbox like Vert.x: fighting against it by forcing blocking code, for instance, will just lead to other bigger problems. For instance, blocking the event loop just means that you don’t serve any more requests!

I’ve tried to bench a bit the service, and as expected, it reacts very well to concurrency just with one event loop thread. The real win that we have here is that every single user is never waiting! It can be slower, but the download rate will be the same for each user, whatever the size of the generated ZIP file. The pressure on the memory is not huge either: it is capped by the size of each file and the size of the zip TOC as it is written at the end (a few KB). I’ll probably try to run some more precise benches to identify the various key limiting factors.

You will find the code of ZipGenerator.java in the referenced Github project.

References

- The sample project: https://github.com/dmetzler/vertx-zip-async

- An introduction to Vert.x: https://vertx.io/docs/guide-for-java-devs/